The Ferruccio Mestrovich Collection

The collection contains a nucleus of sixteen paintings, all of high quality. There are two major works by Iacopo Tintoretto, an altar-piece of striking intensity and an austere portrait. Particularly noteworthy is a glowing and intimate “Sacra Conversazione” by Bonifacio de’ Pitati; in addition, there are other works by Benedetto Diana, Lelio Orsi, Jacopo Amigoni, Francesco Guardi and Alessandro Longhi, two “soprarchi” (paintings above an arch) by Benedetto Carpaccio, son and follower of Vittore and a small panel by Cima da Conegliano. The Mestrovichs belong to an ancient Dalmatian family originally from Zara and have lived in Venice since 1945. The head of the family, Aldo (1885-1969) was persecuted during the Austrian rule for his Italian patriotism; his assets were confiscated by the Yugoslav government and never returned. His son Audace worked for many years in Venice as a lawyer. His youngest son, Ferruccio, a passionate scholar of early Veneto painting, is the donor of this collection: the attributions of the paintings are the result of his research and studies; indeed, his suggestions and indications have assisted several scholars on many occasions in the publication of his paintings and other collections.

Exhibition layout and contents

1. Benedetto Diana (Venice, 1460 ca. – 1525)

Christ Benedictory (oil on wood, 60 x 52,5 cm)

Details of the person and work of Benedetto Rusconi, called Diana, are still fairly unclear. The hypothesis that he studied under Lazzaro Bastiani has been dismissed, and an initial relationship with the conservative milieu of the Murano circle regarded as substantially unimportant. In light of these factors, and the original experimentation evident in his works, critics have tended towards the belief that the young painter was mainly influenced by the work of Giovanni Bellini. Indeed, around 1480, in the years we must assume Benedetto began working independently, Bellini had fully defined his own absolutely revolutionary language. And although it may be true that Diana perhaps never managed to completely appreciate the importance of Bellini’s innovations, it is equally true that a talented young artist beginning his career at that particular time could not but demonstrate a specific interest in the major figure of his contemporary Venetian art world. This hypothesis is supported by an examination of what is regarded as Diana’s earliest work: the Christ Transfigured, previously in Miami and now in the Kress Collection at Coral Gables in Florida. This is an evident derivation, though with some variants, of the similar image in the panel with the Transfiguration painted by Giovanni Bellini in 1480 and conserved in the Capodimonte Museum in Naples. This work by Diana is rather interesting in that it highlights how the young painter had carefully considered the innovations of the most recent Venetian painting: the works of Bellini, obviously, but also those of Antonello da Messina and Carpaccio. The Mestrovich panel has quite similar characteristics, though expressed in a much more evolved and refined style, which could constitute the subsequent stage in the maturing of Benedetto’s language towards a stylistic refinement of very notable expressiveness. Notwithstanding the premises made so far, an additional interest in the works of northern artists active in Venice at the end of the century would also here seem possible. In this sense, a very interesting comparison may be made with the signed image of Christ Benedictory painted by Diana at the end of the century and now in the National Gallery, London. There are significant similarities in the arrangement of the figures – evidently derived from the layout popularised in Venice by Antonello; in the attention to the precise rendering of every detail according to northern traditions; and in the use of a low light similar to that of Carpaccio and Bellini. So, on the basis of these observations, the hypothesis that the panel in the Mestrovich collection is also part of Benedetto Diana’s pictorial catalogue, with a chronology close to that of similar images now in England, seems, with the current level of knowledge, the most probable.

2. Benedetto Carpaccio (Venice, ante 1500 – Capodistria, post 1560)

Announcing Angel and Announced Virgin (oil on canvas, 99 x 103 cm each)

Research carried out by Mestrovich himself, to which Lino Moretti also contributed, has shown that the two segments were originally part of an altarpiece depicting The Glory of the Name of Jesus and Saints, by Benedetto Carpaccio, son of the celebrated Vittore. This work is signed and dated 1541 and was originally exhibited on a wooden altar in the church of Sant’Anna in Capodistria. Indeed, the local historian Baccio Ziliotto (1910) notes that ‘the picture (the altarpiece by Benedetto) was originally completed by three other sections that have now become part of the Basilio collection: an Annunciation was represented in two lateral sections and an Eternal Father in an upper section. But in a period of less intelligent care, they were removed to fit the painting onto the new altar which replaced the older, stouter one made of wood’. These comments are also confirmed by Santangelo in his ‘Inventory of things of art in the province of Pola’ printed in 1935. The section with the figure of the Eternal Father, ‘seen from the front, with long hair and flowing beard, amongst clouds of little purple cherubs, blessing with the right, and in the left holding the globe of the world’ appeared in the First Exposition of Ancient Art organised in 1924 by the Trieste Art Circle under the direction of Antonio Morassi. The current whereabouts of the Eternal Father is unknown; while the two segments, which were not exhibited at the exposition, subsequently went from the Basilio collection in Trieste to that of Dionisio Brugnera in Treviso, from where they were bought by Mestrovich. So there is no doubt that with their confirmed attribution and certain dating, the two canvases represent a dependable benchmark in reconstructing the pictorial catalogue of Vittore’s son and collaborator. The close reference to the stylistic and figurative models of his father are evident in these: in particular, the figure of the Announced Virgin derives from a pictorial model by Vittore, also used by Palma il Vecchio in the panel now in Berlin. The chromatic range played out on dark tones is also noteworthy, along with the use of low lighting which enhances the clarity of the figure and of the clothing. The work is certainly a ‘latecomer’ compared to the great examples of contemporary Venetian painting; it is nevertheless of interesting quality, in the precise description of the figures and objects, in the quality of the colour and in the expression of religious sentiment.

3. Giambattista Cima da Conegliano (Conegliano, 1459/60 – 1517)

Dead Christ (oil on wood, 22 x 15,5 cm)

There is no doubt that this small painting in oil on wood was originally the tabernacle shutter for an altar in an unknown church. It came from the Correr collection and is attributed to Cima da Conegliano by Professor Giuseppe Botta, supervisor of the Venetian Galleries, dating from 19 July 1886, provided at the request of the then owners. Such attribution has also found agreement amongst the numerous critics who, in more recent times, have had the opportunity to directly examine the until now unpublished painting. Born in the Treviso area, Conegliano worked for many years in Venice where he achieved great success, especially with his religious images set in tranquil, expansive landscapes and marked by bright and lively colouring. Small images of religious subjects are not rare in Giambattista Cima’s pictorial catalogue; the theme of Dead Christ in particular was attempted several times by the painter. Proof of this interest remains in the tablet conserved in the City Art Museum and Art Gallery of Birmingham. Like that belonging to Mestrovich, this also originally acted as an altar tabernacle shutter. Although smaller and heavily repainted, the pictorial characteristics of the small work kept in the English museum are of a notable level, on a par with those of the Venetian version. But it is the comparison with another work of the same subject painted by Giambattista that is decisive in attributing the Mestrovich panel to his catalogue: the central section of the polyptych frieze in the San Francesco convent church in Miglionico, near Matera, taken there at the end of the 16th century after being purchased in Venice by Don Marcantonio Mizzoni. Indeed, the correspondence between the pictorial writing, the modelling of the slumped body and even the face and thick head of hair are quite astounding. The polyptych was painted in 1499, as shown by the date inscribed next to the painter’s signature on the base of the central panel, and the perfect similarity of style in the two works allows the Venetian panel to be confidently dated to the same period.

4. Bonifacio De’ Pitati (Verona, 1487 – Venice, 1553)

Holy Conversation (oil on wood, 86 x 139 cm)

This panel, published by Mestrovich himself in the volume of essays in honour of Egidio Martini, came from a private English collection. It depicts an extremely sweet Virgin holding the Child in her arms, with Saints Jerome and John the Baptist on her right, intently meditating on the Holy Scriptures, Peter on her left, offering the Child the keys, and a martyr Saint who could perhaps be identified as Catherine of Alexandria. The background consists of imposing arched architecture decorated with statues placed in the niches, and from which sections of bright sky emerge. On the extreme right there is an exceptional view insert, with a fanciful image of Venice in which the bell-tower and domes of the St. Mark’s Basilica can be seen in distance, amid the waters and shoals of the lagoon. A noble coat of arms (certainly that of the house of the unknown patron who commissioned the work) held up by a marble putto appears on the pillar at the extreme left, along with an inscription that is unfortunately no longer legible. The holy conversation was one of Bonifacio’s favourite themes and one he repeated several times: in all these paintings the characters, typologically clearly defined, are always portrayed in a calm, serene atmosphere, engrossed in a silent conversation of gestures and looks which enhances the mysticism of the figuration. The painter achieves this tranquil world by highly personal formal means, through a simple but fairly lively play of colours and perfectly balanced composition. In this case, too, the scenic layout of the work derives from a typology becoming accepted at the beginning of the 16th century, on the examples of Palma il Vecchio, who was Bonifacio’s most important teacher, and Titian. But the character and sentiment that animate it seem quite original compared to the models of those artists. Bonifacio’s painting differs in fact from that of the other great early 16th century Venetian artists by his particular brand of warm, sweet colourist musicality, played out on tonalism and the fluid juxtaposition of coloured areas imbued with light. Although Bonifacio’s pictorial history still presents some difficulties of chronological definition, it seems quite probable that this splendid painting may be dated to the second half of the 1520s, given that it shows stylistic features and a pictorial technique similar to those in some of his fundamental works which critics have placed in this same period: for example, the Holy Family with Saints Elizabeth, the Infant St John the Baptist and Two Shepherds in the County Museum of Art in Los Angeles and, even more so, the Holy Conversation with Saints in the Louvre.

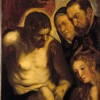

5. Jacopo Tintoretto (Venice, 1519 – 1594)

Christ taken down from the Cross supported by St John and Mary Magdalene in the presence of two Donors (oil on arched canvas, 140 x 70 cm)

The altarpiece was evidently intended for the small private chapel of a family whose members are shown in the painting. The work was noted by Pallucchini in 1969 and his attribution to Jacopo has been unanimously agreed by the critics. Pallucchini’s dating also seems fully acceptable: to a period between 1559, when Jacopo painted the Miracle of the Lame Man for the Venetian church of San Rocco, and 1562, the date shown on the canvas depicting Christ and the Pharisee in the Padua Civic Museum. Indeed, the stylistic and figurative similarities with these works and others painted by Tintoretto in the same period are extremely close. Buy beyond the indisputable attribution of the work, it is important to underline the exceptional quality of the pictorial execution and the stupendously effective portrayal of sentiment. Jacopo is extremely skilled in overcoming the restrictions created by the forced dimensions of the painting. He here gives particular relevance to the now lifeless body of Christ, slumped forward, almost on the diagonal, and this allows him to insert the figures of the donors and that of the Magdalene on the right, offering excellent proof of his splendid portraitist skills. The faces of Christ and St. John are only glimpsed in the half shadow caused by their own forward movements. The faces of the other three people – the two patrons and the beautiful Magdalene who holds Christ’s right foot in one hand and is drawing the other to her breast – are rather caught in full light and depicted with absolute precision. The impression is that this difference is not by chance, but intended to emphasise the two different realities: that of the world of religion in the two figures on the left, and that of the real world in the group of three people arranged on the right. It is therefore possible that this work, pervaded by a sense of profound suffering and tragic sense of death, to which even the bright quality of the light offers no relief, may have a profound significance that goes beyond the mere exterior evidence. Indeed, I would not exclude the possibility that in this altarpiece Tintoretto was asked to record a tragic event: the death of the daughter – depicted in the Magdalene, who may have been her namesake – of the elderly couple who meditate, distraught, on the wan figure of Christ just taken down from the Cross.

6. Jacopo Tintoretto (Venice, 1519 – 1594)

Portrait of Francesco Gherardini (oil on canvas, 70 x 60 cm)

This magnificent painting, undoubtedly one of Tintoretto’s greatest portrait achievements, was noted by Paola Rossi in 1969. Thanks to the correct interpretation of the inscription at top right, which reads ‘FRANC.O GHER / JJ / NACQUE DI / XBRIO 1498 / RITRATO / 1568’, Pizzamano (1992) managed to identify the person portrayed as the Lendinara nobleman, Francesco Gherardini, who died on 28 January 1575 at the age of 77. The close and longstanding relationship between Tintoretto and Gherardini may be confirmed by the appearance of the latter at a relatively young age in another painting by Jacopo: the altarpiece with The Virgin and Child in Glory, with Saints Francis, Antony and Louis and the Donor (the latter being Francesco Gherardini) originally on the main altar of the church dedicated to St. Francis in Lendinara. After this was deconsecrated and subsequently demolished in 1785, the painting passed to various owners before arriving at the Musée de la Villa di Narbonne, where it was incorrectly believed to have been by Paolo Veronese. Gherardini is shown at a later stage of life, at the age of 70, in the Mestrovich portrait. The still imposing figure, dressed in black velvet with crease-edges defined by brisk highlights of whitening, emerges with great vividness and firm plasticity from the neutral background in keeping with Jacopo’s typical portrait style, particularly that of the 7th and 8th decades. The description of the features on the contemplative face are meticulously precise and rendered with a warm colouring, underscored and highlighted by the ‘appeal’ of the white pleated collar emerging from the dark clothes. As Rossi properly points out, ‘the benevolently acute examination which seems to identify the subject gives the work a share in that human warmth typical not only of Tintoretto’s portraits but the greater part of his entire production’.

7. Francesco Beccaruzzi (Conegliano, 1492 ca. – 1563)

St. Francis (oil on canvas, 192 x 125 cm)

Nothing is known about the origin of this altarpiece, which was part of the rich collection belonging to the Caregiani family of Venice ab antiquo. Attribution of this fine example of expressive precision to Francesco Beccaruzzi is based on the similarity of stylistic features to other works unanimously referred to the Treviso painter. One document shows that he was in Treviso in 1519, the year Pordenone began work on the fresco decoration of the Malchiostro family chapel in the apse of the cathedral, which was soon after joined by Titian’s altarpiece. And, in addition to a certain influence from his contemporary Paris Bordon, Pordenone and Titian were precisely those artists who most conditioned Beccaruzzi’s artistic education and development. This can be clearly seen in works such as the altarpiece painted for the church of San Francesco in Conegliano (now in the cathedral of the same city) portraying St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata and Six Saints, completed in 1545. The same stylistic features also appear in the Mestrovich canvas. Pordenone seems clearly evoked in the monumentality of the single, grandiose figure; while the world of Titian is easy to make out: not only in the austere naturalistic conformation opening up behind the saint, but also in some lexical citations, such as the hand Francis draws to his breast, which may be more or less superimposed on that of the Virgin Annunciata in the Malchiostro chapel altarpiece with its unnaturally long fingers. More simple comparisons between the pictorial execution of the Mestrovich altarpiece and that in Conegliano are also significant and absolutely compelling: the lengthened unfolding of St. Francis’ habit is repeated almost exactly in that of St. Antony. Despite being caught from opposing views, these two figures can be virtually superimposed. In both paintings the sky is crossed by thin, fairly bright, horizontally-moving clouds, while the treatment of the foliage is identical. All these elements attest not only to these works being by the same hand, but also to their proximity of execution in the middle of the fifth decade.

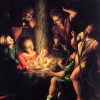

8. Lelio Orsi (Novellara, 1508 ca. – 1587)

Adoration of the Shepherds (oil on wood, 52,5 x 35,5 cm)

Lelio Orsi was one of the most singular and imaginative leaders of Emilian Mannerism. His structured pictorial knowledge is closely linked to that of the world of Correggio and Parmigianino, as well as to the Mantuan artistic circle, updated by the presence of Giulio Romano, and that of Michelangelo in Rome, with which the Novellare painter had direct contacts during his stay in the papal city in 1554-5. This small panel is an excellent example of his limited and precious production. Previously unpublished, it is, however, well known to scholars, having been examined and appreciated by Ugo Ruggeri, Vittorio Sgarbi, Alessandro Ballarin and the present writer, amongst others. It is evidently inspired by the Night painted by Correggio for the basilica of San Prospero in Reggio Emilia (where Orsi long worked), now in the Gemaldegalierie in Dresden. But the interpretation Orsi gives of this theme is absolutely personal and very skilfully executed. The quality of the painting is intensified by the brilliant chromatism that almost makes the figures – most of which are caught in Manneristically dynamic poses – leap out, with a recurring use of ‘contrast’ with the ‘false night’ setting. In the fairly limited catalogue of paintings known to be by Orsi, it is easy to find works with compelling and significant similarities to the Mestrovich panel, confirming its attribution to the Emilian artist. For example, the Adoration of the Shepherds, previously in the Podio collection, Bologna, where the drapery of the shepherds’ clothing and the elegantly articulated design of the hands are quite analogous; similarly with the types of head: that of the shepherd on the extreme right could virtually be superimposed on that of the St Joseph depicted in the ex-Podio painting. Then there is the Virgin and Child with the Infant St. John in the Rizzi collection in Sestri Levante, where there is an evident and very close similarity in the portrayal of the Virgin’s face. These are all works in which Orsi’s meditations on Correggio’s examples seem to be filtered through a direct knowledge of the Roman Mannerist world, most evident in his work after his trip to Rome in the middle of the sixth decade. There is therefore no doubt that the execution of this exceptional Adoration of the Shepherds must also be placed in a period shortly after this.

9. Jacopo Amigoni (Venice, 1682 – Madrid, 1752)

Portrait of a Young Woman (the ‘debutante’) (oil on canvas, 108,5 x 84 cm)

10. Jacopo Amigoni (Venice, 1682 – Madrid, 1752)

Portrait of a Lady (oil on canvas, 109 x 85,5 cm)

These two paintings of the same size and stylistic character were formerly part of a private Tuscan collection. Only one of them – that of the younger lady – is mentioned in literature, having been published by G.M. Pilo in 1958 with the title ‘Portrait of a Debutante’. The scholar’s attribution to Amigoni at that time was also unhesitatingly accepted by A. Scarpa Sonino (1994) and is based on totally credible reasons, such as the particular elegance of the staging, the extreme refinement of the chromatic impasto, tending to highlight the details of the elegant dress, the subtlety of the psychological definition and the exceptionally skilful portrayal of the facial features (‘gaze of velvet in purest alabaster, touched only by the pink of the lips’, according to Pilo’s delightful description). And it goes without saying that this must also be extended to its pendant, which has identical qualities. The two portraits can probably be dated to the artist’s last stay in Venice, between 1739 and 1747, when he definitively abandoned his home city to move to Madrid. This is testified by their absolute executive similarity to works known to be from this period, such as, for example, the portraits of Maria Barbara di Braganza, Queen of Spain, in the collection of the marquess of Canossa, Verona, or that of the merchant Sigmund Streit, now in Berlin, dating from about 1740. It is not possible to say who the two women painted by Amigoni were, but the hypothesis suggested by Scarpa Sonino is quite fascinating. He notes an ‘astounding similarity’ in the portrait of the younger lady to the soprano Teresa Castellini, who appears in the canvas with The Eunuch Farinelli and his Friends painted by Amigoni in Madrid between 1750 and 1752, now in Melbourne. On the other hand, the same scholar emphasises the need to find other elements to give weight to this hypothesis, particularly regarding the possibility of a meeting between the artist and the singer before the time of their both being in Madrid.

11. Alessandro Longhi (Venice, 1733 – 1813)

Portrait of Giuseppe Chiribiri (Cherubini) (oil on canvas, 83,5 x 65 cm)

The portrait carries an 18th century inscription on the back of the original canvas (‘Ritratto dell’ Ab.e / Giuseppe Di / Cherubini / Alessandro Longhi / Agosto 1779’) which, beyond the quite convincing stylistic evidence, certifies the identity of both artist and subject, and the date of the work. Alessandro Longhi’s intensive work includes numerous ‘bourgeois’ portraits, all distinguished by a remarkable compositional felicity that is in perfect harmony with his desire to bring out the affable nature of his subjects. The images of theatre people like Carlo Goldoni, painters like Andrea Urbani, professionals like Doctor Gian Pietro Pellegrini, mariners like Captain Pietro Budinich, prelates like the Reverend Sante Bonelli and many others thus make up an exceptional gallery of the ‘minor’ characters of Venice in the second half of the 18th century. They are all depicted with meticulous care in the rendering of their facial features, clothes, and the salient elements of their activity; and with an innate tendency to emphasise aspects of their character in a positive light. But, even more so, as is well shown by the portrait of Giuseppe Chiribiri, with an exceptional pictorial quality marked by the brightness and richness of the colour and the elegance of the conformation. According to research carried out by Mestrovich himself, to which Lino Moretti also contributed, the subject here is a person of some importance in the Venetian literary world of the mid-18th century. Born in Giudecca on 7 September 1738 into a middle-class family, he made his debut as a poet when just 17, at which time he decided to change his name to Cherubini. Donning clerical robes, he joined the circle of the Granelleschi, establishing a lasting friendship with Gasparo and Carlo Gozzi. He published his main work, ‘Poesie bernesche’ (Satyrical Poems) in 1767, which show his lively polemical views on contemporary customs and fashions, amongst which he also included the theatre of Goldoni, and on women and marriage. The volume was edited by Antonio Graziosi and carries an engraving as a frontispiece taken from another portrait of the poet, also by Alessandro. A collection of moral essays appeared in the same year under the title ‘I miei pensieri’ (‘My Thoughts’). On becoming a priest, he took over the parish of Angelo Raffaele and thus renounced poetry, applying himself rather to an intensive career as a preacher. He died at a little over fifty on 8 August 1790.

12. Francesco Guardi (Venice, 1712 – 1793)

Dressed Madonna (oil on canvas, 100 x 82 cm)

From about the mid-1760, probably coinciding with the return of tourists to Venice after the end of the Austrian war of succession, Francesco Guardi turned his interest mainly towards the painting of views and landscapes – in demand by foreign clients. But this new situation did not preclude him from continuing his previous work as a painter of religious and historical works and of portraits. This very rare image of what, according to popular Venetian tradition, was called a ‘Dressed Madonna’, may easily be placed amongst the paintings dating from this later period in the artist’s career. Actually, such images were usually painted on wood for carrying on the shoulders during religious processions, according to a custom adopted from Austria and Spain, and which had some following also in Venice. A splendid example of these, used during the rosary procession, remains in the first altar on the left in the church of the Gesuati, the throne of which was sculpted by one of the foremost Venetian wood-carvers of the time, Francesco Bernardoni (1669-1730). The painting by Francesco Guardi also portrays a Madonna, richly dressed in 18th century fashion, crowned and carrying a rosary in her left hand. The Child, also carrying a rosary, is similarly crowned and dressed as a young scion of the highest Venetian society of the time. It is therefore evident that it, too, like the wooden group by Bernardino, was originally intended for a religious order particularly devoted to the rosary, such as the Dominicans in particular. Leaving aside the oddity of its iconography, the pictorial quality of the canvas is considerable. The elegant, elaborate decoration of the Virgin’s rich dress is executed in a very similar manner to the pictorial styles seen in the uniform worn by the Youth from the Gradenigo Family in the portrait at the Museum of Fine Arts in Springfield, painted by Francesco. The paired heads of cherubs that peep out here and there correspond perfectly to those in the altarpiece in the Roncegno parish church, painted for the Giovanelli in the second half of the 1780. But the painting of the details of the rosaries is particularly exquisite, done with the brush tip using very bright paint, in a style reminiscent particularly of Francesco’s elder brother, Antonio, his early teacher.

13. Ubaldo Gandolfi (San Matteo della Decima, 1728 – Ravenna, 1781)

St. Jerome meditating on the Crucifix (oil on canvas, 117 x 96,5 cm)

Ubaldo Gandolfi received his training in Bologna at the Clementina Academy, along with Torelli, Graziani and the Lelli. The young artist there had the opportunity to learn about and appreciate the great tradition of local painting, from the Carracci and Guido Reni, through to Pasinelli, Creti and dal Sole. Ubaldo’s younger brother, Gaetano, went to Venice in 1760 where he had the chance to come into direct contact not only with the works of his contemporaries, but also the finest examples of 16th century Venetian art, and was particularly struck by the colouring typical of those masters. It is not known for certain if and when Ubaldo made the same trip. There is, however, no doubt that he also became fascinated by the Venetian world from about this time. He was attracted by the form and colour typical of these artists, and from these same years began conducting his own genuine research, advancing Venetian suggestions. The vivid colouring of the Mestrovich painting undoubtedly relates to this world, particularly evident in the bright red of the saint’s cloak. On the other hand, a Bolognese style is more evident in the concentrated volumetry of the vigorous figure. Jerome is presented in the foreground in a dynamically powerful pose, dramatically lit by a low light from the right, fully highlighting the wooden cross while putting part of St. Jerome’s face and body in the shade. The most credible date for this painting would thus seem to be around 1763-5. The iconographic elements typical of the saint are reduced to the minimum in this canvas: the cardinal’s hat and the lion, the usual symbols in the current iconography are both missing. What remains is the Cross, on which Jerome is meditating, and the stone, with which he strikes himself for purification from the sins of the flesh. The presence of the small landscape section at top left is significant: some foreshortened buildings are just outlined on the crest of an incline, and are probably a church and an obelisk. These are the symbols of eternal salvation, which man may only reach by overcoming the weakness of the flesh, via an extremely difficult path.

14. Paolo Scorzia

Board for the ‘royal game’ (oil on canvas, 86,5 x 105 cm)

The Venetian propensity for gambling is well known, and not a few family fortunes were lost at the Ridotto in Palazzo Dandolo at San Moisè – the place designated by the government itself for such activities from 1638 – at the private casinos of the nobility or, more simply, in the bars and on the street. Numerous games were played with cards, dice and boards: some of the more famous being basset, faro, thirty and forty, biribisso, Greek gilè, piquet, three-seven and backgammon, which often had rules quite similar to those played today, though perhaps had different names. The royal game was a kind of lottery: it required a board – sometimes painted on wood, but usually on canvas (or carved then glued onto canvas) so it could be rolled up for easier transportation – and a dice cup of tokens carrying the same numbers and designs as those shown on the board. The feature of this game was that bets could be laid not only on the individual numbers, but also on odds and evens, and on rows and columns, thus making it a kind of forerunner to modern roulette. The board in the Mestrovich collection is divided into 90 boxes, each one bearing a different picture: of men and women, of noble coats of arms, animals, flowers and fruit. At the top it has a brief summary of the rules of the game: ‘SE GIOCATO NON RIAVETE I DENARI, NON PUOI A ORO COPERTO, NON SI PAGA SE AVETE BARATO / GIOCANDO A LA BASETTA LE OTTO FACIE CIOUE’ N. 1,9,31,33,19,51,82,90 SONO DEL BANCO’ (If you don’t win, you can’t play on credit, payment is not made if you’ve cheated / in the game of basetta, the 8 numbers 1,9,31,33,19,51,82,90 are the bank’s); on both sides it has boxes for bets on groups of numbers (‘DENTRO / PARO / DISPARO / FUORI’) (‘IN / EVEN / ODD / OUT’). The significance of this particular board is that it is the only one not painted anonymously: the signature ‘Paulus Scortia fecit’, appears in a scroll in box number 4, under a noble coat of arms that is presumably invented, given that it has no reference to Veneto nobility. This is an otherwise unknown artist, but one who was certainly gifted with a delightful popular streak and pleasant colouring skills.

The donation was expanded on October 2009 with an additional 14 outstanding paintings, of different periods and subjects, from the late Sixteenth century to today.

Carletto Caliari (1570 – 1596)

Annunciazione

Giovan Francesco Barbieri detto il Guercino (1591-1666)

Jaele e Sisara

Girolamo Forabosco (1604/5 – 1679)

Ritratto del doge Domenico II Contarini

Sebastiano Ricci (1659 – 1734)

Susanna e i vecchioni

Antonio Balestra (1666 – 1740)

Agar e Ismaele nel deserto

Antonio Guardi (1699 – 1760)

Lot e le figlie

Giuseppe Abbati (1836 – 1868)

Marina di Vada

Federico Zandomeneghi (1841 – 1917)

Donna con bambino seduti in un bosco

Egisto Lancerotto (1847 – 1916)

Nudo di donna

Egisto Lancerotto (1847 – 1916)

Giovane donna in piedi

Egisto Lancerotto (1847 – 1916)

Ritratto di giovane donna con rosa sui capelli

Alessandro Milesi (1856 – 1945)

Fanciulla con bambino in braccio

Emma Ciardi (1879 – 1933)

Veduta del bacino di San Marco

Pietro Marusig (1879 – 1937)

Natura morta